Drawing A Triangle 7 Ways

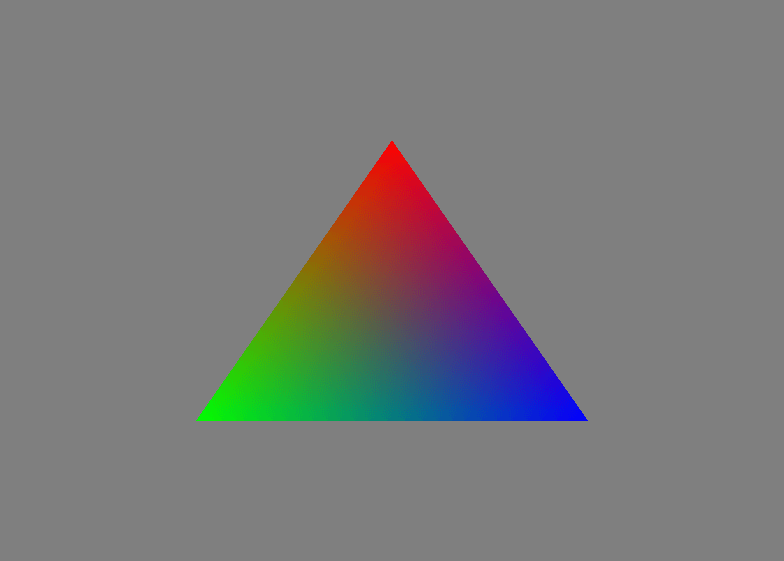

The "Hello, World" of graphics programming is a program that displays a triangle to the screen. It looks like this:

I'll be drawing the exact same triangle for the following APIs/libraries, comparing their similarities and differences:

All of the programs handle window resizing, stretching the triangle when the window size increases, and squishing the triangle when the window size decreases. All programs involve a vertex buffer with position and color information. No vertex information is stored in shader code. That's cheating. The programs don't perform a "proper" teardown since most of the resources, like window handles and pipelines, lives for the entire lifetime of the program.

SDL2 + OpenGL

I think most people who get into graphics programming today are introduced to it through OpenGL, thanks in no small part to Learn OpenGL. Despite its age and deprecated status on macOS, it's still a decent API for learning graphics and remains popular to this day. The code example uses OpenGL 3.3, the same version used in Learn OpenGL.

OpenGL either hides/abstracts things that other APIs freely expose, or it

makes the windowing API responsible for the graphics behavior. With SDL2 and

OpenGL, swapping the back/front buffers happens through SDL_GL_SwapWindow.

In other APIs like D3D11, The swap chain object is responsible for presenting

and swapping the image buffers.

One of the pain points about OpenGL is that you'll need a loading library such

as glad or GLEW to

access the modern OpenGL functions (by modern, I mean VAOs and shaders, not

DSA). Loading these functions differs depending on the platform/library. For

example, SDL2 has SDL_GL_GetProcAddress, Linux has X11 has

glXGetProcAddress. For Windows, you'll need to create an invisible dummy

window to get the wglGetProcAddress function before creating your actual

application window.

I picked SDL2 for setting up a window and OpenGL context. Both SDL2 and OpenGL support many different platforms, so they pair very well together. The next few examples also uses SDL2 for the same reason.

SDL2 + WebGPU

As of writing this, the only browser that supports WebGPU out of the box is Chrome. But the WebGPU API is also accessible on desktop through Dawn or wgpu.

Again, I'm using SDL2 for window creation because of its cross platform support. WebGPU is also cross platform by unifying access to the GPU, building on top of platform specific APIs like Metal, and D3D12.

Metal, Direct3D, and Vulkan all differ when it comes to shading languages. Metal has MSL, Direct3D 11 and 12 has HLSL, and Vulkan uses SPIR-V bytecode which can be compiled from GLSL. WebGPU introduces its own shader language called WGSL (WebGPU Shading Language), and it looks like this:

struct VertexIn {

@location(0) position: vec3f,

@location(1) color: vec4f,

}

struct VertexOut {

@builtin(position) position: vec4f,

@location(1) color: vec4f,

}

@vertex fn vs_main(in: VertexIn) -> VertexOut {

var out: VertexOut;

out.position = vec4f(in.position, 1.0f);

out.color = in.color;

return out;

}

@fragment fn fs_main(in: VertexOut) -> @location(0) vec4f {

return in.color;

}Compared to OpenGL, you'll need to perform more housekeeping with WebGPU. You'll work with swap chains, render pipelines, command buffers, and queues. Even though there's more control with the hardware, the abstraction level is high level enough to be used by mortals such as myself.

You'll need a WGPUSurface window surface to draw on, which depends on an OS

specific window handle (HWND on Windows, Display * and Window for X11

on Linux). Getting the window handle to create a surface is the only platform

specific code path needed to draw a triangle.

Because WebGPU is designed for the web, you'll need to wait for asynchronous

callbacks to finish. It differs depending on the implementation. For Dawn,

you'll have to call wgpuDeviceTick. wgpu uses wgpuDevicePoll. The

JavaScript API doesn't have this, because the browser has an event loop.

Although it's early days for WebGPU, I'm optimistic with what it could bring to both the web and on desktop.

SDL2 + Vulkan

Vulkan is known for being difficult to learn, especially for beginners. Writing over 800 lines of C++ to draw a triangle on the screen just does not spark joy to some people.

Learning materials such as Vulkan Tutorial mention downloading the Vulkan SDK when setting up a development environment. The setup is more involved than I would like, but there exists a Vulkan loader that doesn't need the official SDK to build your program. It's called vkbind and it's made by the same person behind miniaudio.

Even with vkbind, you might want to install the SDK anyways. Vulkan uses a

bytecode format called SPIR-V when creating shaders programs and the SDK

provides glslangValidator, a program that converts human readable GLSL to

SPIR-V. This means building a Vulkan application is at least a two step

process. Build the shaders first, then the actual program. There are ways to

compile to SPIR-V at runtime but it's typical to compile offline so you don't

distribute GLSL as part of your application.

For all of the code examples, I tried to keep the C++ features to a minimum,

making it easier to translate to C if needed. The Vulkan example is the only

example that uses the STL (std::vector). Some of the Vulkan functions

involve calling it once for an item count, and again to actually fill up a

buffer of items. Doing this without std::vector just adds friction to what

is already a lot of code for drawing a triangle.

// with std::vector

uint32_t count = 0;

vkEnumeratePhysicalDevices(instance, &count, nullptr);

std::vector<VkPhysicalDevice> physical_devices(count);

vkEnumeratePhysicalDevices(instance, &count, physical_devices.data());

// with malloc

uint32_t count = 0;

vkEnumeratePhysicalDevices(instance, &count, nullptr);

VkPhysicalDevice *physical_devices =

(VkPhysicalDevice *)malloc(count * sizeof(VkPhysicalDevice));

vkEnumeratePhysicalDevices(instance, &count, physical_devices);

// then probably a few lines below, a call to free()For the malloc snippet, I had to type VkPhysicalDevice three times. Once

time for the variable, another for sizeof, and a third time because C++

doesn't like conversions from void *. Spreading this pattern across

hundreds of lines was not someone I was up for. In retrospect, I could have

used fixed sized buffers with an extra length variable for each buffer

instead.

Vulkan tries to be cross platform, but because Apple wants a closed off environment for macOS and iOS, Vulkan is only native for Windows, Linux, and Android. You'll need to use MoltenVK to act as a translation layer between Vulkan and Metal if you want to talk to macOS machines.

Just like WebGPU, the only platform specific code path to draw a triangle is

to get the OS window handle for VkSurfaceKHR window surface creation.

Handing window resize requires more work compared to OpenGL and WebGPU. In

OpenGL you just call glViewport. In WebGPU, you recreate the swap chain. In

Vulkan, you have to recreate the swap chain, as well as a collection of frame

buffers and image views associated with the swap chain.

Vulkan also provides synchronization primitives since the GPU is doing work asynchronously. Getting an image from the swap chain needs to be synchronized with semaphores and waiting on the GPU to finish commands is done with fences.

Win32 + Direct3D 11

I really wish there was a Learn OpenGL equivalent for D3D11. It's a very pleasant API to use, and I would work with it more if it weren't for the fact that D3D11 is made for Windows only. Although, people joke that Direct3D is the best cross platform API since Windows users can run it natively, Linux users can run it through Proton, and Mac users run can Windows through Boot Camp.

I'm using Win32 for window creation. Since D3D11 is only native to Windows, it makes sense to use the native windowing API as well. Some OpenGL and Vulkan tutorials describe how horrible the Win32 API is, but the code doesn't look too different compared to a cross platform library like SDL2.

Here is a minimal SDL2 application:

#include <SDL2/SDL.h>

int main() {

SDL_Init(SDL_INIT_VIDEO | SDL_INIT_EVENTS);

int width = 800, height = 600;

SDL_Window *window = SDL_CreateWindow("Window Title", SDL_WINDOWPOS_CENTERED,

SDL_WINDOWPOS_CENTERED, width, height,

SDL_WINDOW_RESIZABLE);

bool should_quit = false;

while (!should_quit) {

SDL_Event e = {};

while (SDL_PollEvent(&e)) {

if (e.type == SDL_QUIT) {

should_quit = true;

}

}

}

}And here is Win32:

#include <windows.h>

LRESULT CALLBACK wnd_proc(HWND hwnd, UINT msg, WPARAM wparam, LPARAM lparam) {

switch (msg) {

case WM_DESTROY:

PostQuitMessage(0);

return 0;

default:

return DefWindowProc(hwnd, msg, wparam, lparam);

}

}

int main() {

const char *title = "Window Title";

WNDCLASSA wc = {};

wc.lpfnWndProc = wnd_proc;

wc.hCursor = LoadCursor(nullptr, IDC_ARROW);

wc.lpszClassName = title;

RegisterClassA(&wc);

int width = 800, height = 600;

HWND hwnd = CreateWindowExA(0, title, title, WS_OVERLAPPEDWINDOW | WS_VISIBLE,

CW_USEDEFAULT, CW_USEDEFAULT, width, height,

nullptr, nullptr, nullptr, nullptr);

bool should_quit = false;

while (!should_quit) {

MSG msg = {};

while (PeekMessage(&msg, nullptr, 0, 0, PM_REMOVE)) {

TranslateMessage(&msg);

DispatchMessage(&msg);

if (msg.message == WM_QUIT) {

should_quit = true;

}

}

}

}They both look similar, but only if you squint. Both Win32 and SDL2 use a

function to create a window, and a loop to poll for events. If you get rid of

the window procedure callback and the call to RegisterClassA, the remaining

differences aren't too far from SDL2.

Direct3D's shader language is HLSL (High-level shader language). One of the advantages of HLSL is that you can write your vertex and pixel shader code in the same file. The same is also true for WGSL. You'll often see that the vertex shader code and fragment shader code are separated into multiple files for OpenGL and Vulkan programs.

You can compile HLSL by calling D3DCompile. The function is accessible by

linking the application with d3dcompiler.lib, but I previously had problems

compiling my program with Clang with that approach. Instead, I dynamically

loaded d3dcompiler_47.dll, and got the function pointer for D3DCompile

from the DLL.

When describing vertex attribute layouts, there's the option to use

D3D11_APPEND_ALIGNED_ELEMENT to say that the attribute begins right after

the previous one. This is pretty convenient, since the vertex attribute

offset doesn't need to be calculated. Unfortunately, some of the convenience

is lost since you need a HLSL semantic name for each vertex attribute.

HTML + WebGL 2

WebGL 2 lets you write graphics applications right in the browser using an API that's close to OpenGL ES 3.0. The benefit of writing for the web is that it's readily available on practically every modern device. WebGL uses ANGLE to translate its API to a platform specific API like Direct3D, OpenGL, or Metal. Deploying your application for the web is a great way to make it reach more people, since users don't have to install an executable to run it natively. Also, if you're learning OpenGL, but you're in an environment where you don't have a compiler, you can still do some graphics programming right in the browser.

The big drawback of WebGL is that the tooling is poor. You won't be running RenderDoc on your WebGL application. You also won't see demanding graphics very often on the web. If high fidelity is the goal, running in the browser might not be a good fit.

The other code examples define a struct for a single vertex, but WebGL expects

a Float32Array when filling in vertex buffer data. Since JavaScript really

doesn't have a way to trivially convert objects to a flat array of numbers,

the vertex attributes aren't neatly grouped up. There's no offsetof, so the

attribute offsets need to be calculated by hand, and since there's no vertex

struct, the vertex stride is hard-coded.

Also, the code looks similar to the SDL2 + OpenGL example, which kind of makes sense I guess.

Sokol

Sokol is a collection of single header

files for C and C++. sokol_gfx.h unifies OpenGL 3.3, WebGL 2, Direct3D 11,

and Metal into a single 3D API. sokol_app.h is a cross platform library

that provides a window to draw onto. The Sokol libraries are dependency free

and are easy to build with. They make heavy use of structs as parameters to

functions. This is fantastic when paired with C99's designated initializers.

sokol_gfx only has five resources that you keep track of: buffers, shaders, pipeline state objects, images, and render passes. It also has good error handling through its validation layer. When using the OpenGL backend, state changes are cached which improves performance.

sokol_gfx doesn't have a cross compatible shader language, but there is a tool called sokol-shdc that translates a GLSL-like file into a C header file that contains shader code for multiple backends. Just like with Vulkan, you'll be doing this offline.

sokol_app makes it incredibly easy to port a C/C++ desktop application to the web with Emscripten. Since sokol_app is mindful of the web as a target platform, the way you write application code also changes. Initialization, event polling, and the update loop is all done through callbacks.

There are tons of examples you can look at to learn Sokol. You'll find examples for offscreen rendering, model loading with cgltf, and ImGui support. There are also language bindings for Zig, Odin, Nim, and Rust.

raylib

raylib is a library for making games in C. It

provides an immediate mode rendering API with rlgl.h which uses OpenGL

under the hood. The raylib code is so short that I can just paste it here:

#include <raylib.h>

#include <rlgl.h>

int main() {

SetConfigFlags(FLAG_WINDOW_RESIZABLE);

InitWindow(800, 600, "raylib + rlgl");

while (!WindowShouldClose()) {

BeginDrawing();

ClearBackground({128, 128, 128, 255});

rlMatrixMode(RL_PROJECTION);

rlLoadIdentity();

rlBegin(RL_TRIANGLES);

rlColor4f(1.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f); rlVertex3f(+0.0f, +0.5f, 0.0f);

rlColor4f(0.0f, 1.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f); rlVertex3f(-0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f);

rlColor4f(0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f, 1.0f); rlVertex3f(+0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f);

rlEnd();

EndDrawing();

}

}Isn't it nice to have a library that just needs two functions for windowing?

InitWindow and WindowShouldClose is all you need.

raylib's rendering API is the same style as OpenGL 1.1. This doesn't mean

raylib is using a version of OpenGL back in 1997. Instead, it wraps multiple

versions of OpenGL, using version 3.3 as the default. Internally, it creates

dynamic vertex buffers that lives on the GPU and arrays of position and color

data that gets written to every time rlVertex3f is called. At the end of

the frame, the buffers are "flushed", transferring the data from memory to

the vertex buffers that live on the GPU.

raylib is at a much higher level of abstraction compared to the previously

explored options. It assumes you'll be drawing things like images and text,

so Raylib starts the program with an orthographic projection that matches the

size of the window. rlMatrixMode(RL_PROJECTION) and rlLoadIdentity() is

called to reset the projection matrix so that the vertex positions will be in

their proper place when its time to draw on the screen.

Because of the way raylib's renderer works, it uses the same shader to draw color filled rectangles and textures that you load from image files. This is only achievable by always having at least one texture bound. When the user draws something with no texture, such as a filled rectangle, it uses an internal 1x1 white texture to sample from.

raylib is very enjoyable to use as a video game library. I can definitely recommend it for beginner programmers who want to make their first few 2D games. The raylib source code is also on GitHub so you can read it to learn more about OpenGL and game framework architecture in C.

Closing Thoughts

Depending on the library/API that you choose, the path to drawing a triangle can either be an easy one (raylib), or a lengthy and difficult one (Vulkan). You have the option for your program run on multiple devices with SDL2, or on specific platforms like Windows, or the browser.

The "Hello, Triangle" program doesn't paint the whole picture of what these APIs give you, and what they need from you when your program increases in complexity. Multisampling is easy with OpenGL, but is a little more involved with Direct3D 11. You probably won't work with uniforms in a library like raylib, but with Vulkan, you'll need to deal with descriptor pools, descriptor sets, and how they interact with shaders.